Necurs is one of the biggest botnets in the world – according to MalwareTech there are a couple millions of infected computers, several hundred thousand of which are online at any given time. Compromised computers send spam email to large number of recipients – usually the messages are created to look like a request to check invoice details or to confirm purchase. The attachments contain packed scripts which install malware when ran. Currently, the dropped ransomware is Locky, which encrypts the hard disk and then asks for money (often in Bitcoin) in order to retrieve the original files. Necurs is an example of hybrid network in terms of Command and Control architecture – a mixture of centralized model (which allows to quickly control the botnet), with peer-to-peer (P2P) model, making it next to impossible to take over the whole botnet by shutting down just a single server. For those reasons, the huge success of Necurs is no surprise.

Behaviour

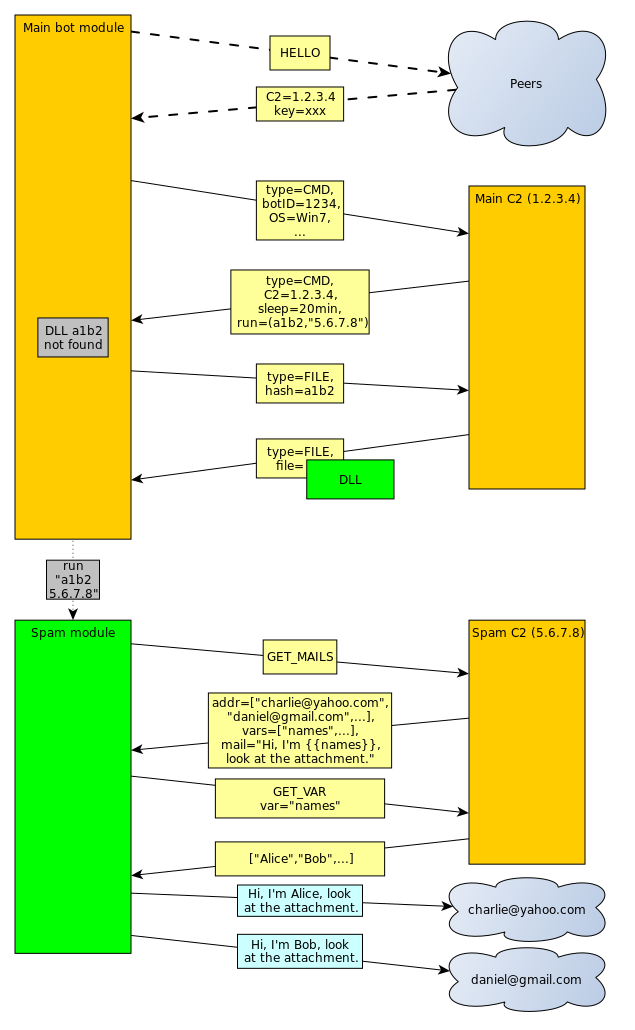

The malware attempts to connect to the C2 server, whose IP address is retrieved in a number of different ways. First, a couple of domains or raw IP addresses are embedded in the program resources (in encrypted form – more about this in the technical analysis section). If the connection fails, Necurs runs domain generation algorithm, crafting up to 2048 pseudorandom names, generation of which depends on current date and seed hardcoded in encrypted resources, and tries them all in a couple of threads. If any of them resolves and responds using the correct protocol, it is saved as a server address. Otherwise, if all these methods fail, C2 domain is retrieved from the P2P network – the initial list of about 2000 peers (in form of IP+port pairs) is hardcoded in the binary. During analysis, Necurs used the last method, since none of the DGA domains was responding. It is however possible, that in the future the botnet’s author will start to register these domains – a new list of potential addresses is generated every 4 days.

After establishing a successful connection to the C2, Necurs downloads (using custom protocol over HTTP) a list of information – from now on, I will call them “resources”. Every resource is identified by a constant 64-bit number. It is quite likely a hash of some sensible name used in source code, but after compilation we obviously cannot access it. Nonetheless, analyzing how these resources are used in the code, we could map some of the IDs to useful names.

Examples of information sent by the C2 include: new P2P neighborhood (ca. 2000 IP:port pairs), new C2 domain list, sleep command (usually about twenty minutes or so), or request to download and run DLL module. Every request we receive contains the sleep request – it is probably a way to reduce the server’s load.

The analyzed binary did not contain what we really sought – mail sending routine. As it turns out, that functionality is in one of the dropped DLLs. Unfortunately, it was written in C++, which increased code size (because the author used C++ templates) and therefore, slowed down reverse engineering. For that reason, we mostly used behavioral analysis – debugging malware and observing sent data (before the encryption of course).

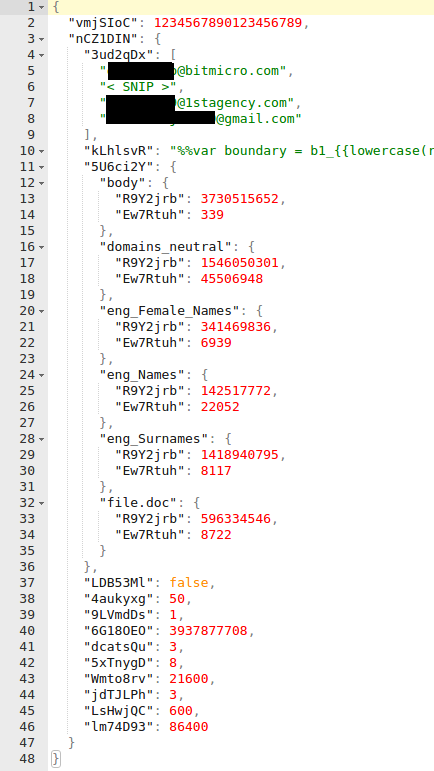

As we could see, the payload is formatted as JSON. Unfortunately all of the keys were obfuscated and it was impossible to discover their meaning just by the name – for example “dg3XGB9” corresponds to the current Unix time. There are a couple of message formats, but not all of them are really interesting. The most important was the request for mail to be sent and of course the server’s response. The text Necurs sends is not just literal email – a simple script language is used to randomize them:

We can see, that the script supports local variables (declared by %%var directive), predefined functions, such as randnum, but there are also references to external data – e.g. [file.doc] – these variables are downloaded in a separate request. We checked the attachments, and despite the name (file.doc), these are ZIP archives containing a single JS file. When executed, they download and run Zepto, a rather new variant of Locky ransomware.

Technical analysis

Necurs uses a couple of anti-analysis techniques. For example, every C2 connection is attempted randomly: either to the address given in function argument, or to the address being a hash of the argument. Virtualization is detected using instructions such as “vmcpuid”, or “in al”. Some malware analysis environments can also fail on checking whether Facebook and random domain resolve to the same IP address. Many texts and binary resources are encrypted – communication with peers and C2 as well.

Resources

Constants in the binary are hidden in a separate section – the file contains two named “.reloc” sections, the second of which contains resources. First four bytes of that section are interpreted as a decryption key, and the resources themselves start at offset 0x18. Every byte is xored with key, which changes according to LCG algorithm: K’=K*0x19661f+0x3c6ef387. After decryption, the data is a list of concatenated structures of the following format:

Last field size is size>>8. Every resource has its unique identifier – examples of resources are initial peer or C2 communication keys or initial peer neighborhood list.

P2P communication

P2P communication is unfortunately much more complicated. All information exchange happens over UDP protocol. The outermost layer of communication is:

Wrapped data are encrypted using the key calculated as a sum of the key field and the first 32 bits of the public key contained in file resources. The homemade encryption algorithm is equivalent to the following Python code:

Checksum sent as second field in the structure is simply a final value of key after encryption. The decrypted data have the following form:

Size of data is size_flag>>4, and the type of the message is determined by four least significant bits of that field. For example, first message (“greeting”) has these bits all zeroed.

The next stage depends on the message type. For the first message, the structure is:

Should the peer respond, the message has the following form:

The whole message is signed using key from file resources. The most important field of this structure is resources – list of resources in the same format as described in “Resources” section. Interestingly, peers don’t send new neighborhood list – these are sent by the C2 itself. The most likely reason for this measure is avoiding P2P poisoning, since it is known that peer list received from the main server is authorized and correct.

C2 communication

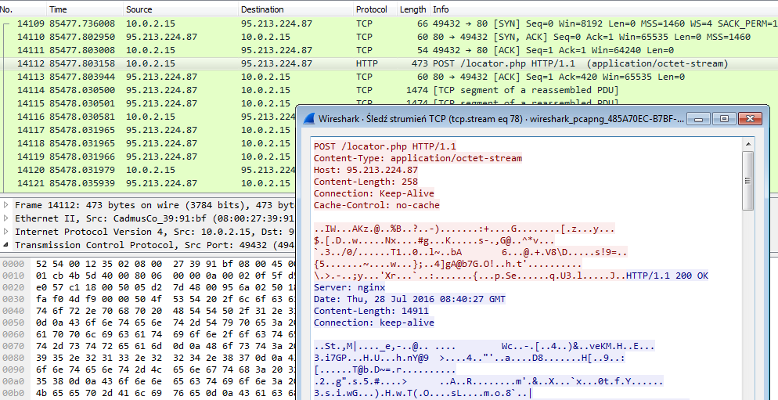

C2 protocol is vaguely similar to the P2P one, but encryption routines and structures it uses are a bit different – also, the underlying protocol is HTTP (POST payload) instead of raw UDP sockets. The first stage is exactly the same (outer_layer structure), with different constants in encryption algorithm:

Decrypted data is of the following structure:

The first field contains randomly generated 8 bytes, probably to increase entropy of sent data and to make it harder to see patterns like common initial bytes across messages.

Contents of the payload field (perhaps compressed, depending on the second bit of flags) depends on message type (command field). If it is file download request (command=1), the payload is simply the SHA-1 hash of the requested file. On the other hand, if the whole message is a periodic command request (command=0), the payload structure is much more complex – again, a kind of list of resources, but with different structure. Every resource has the following general form (can be thought of as header):

Depending on resource type, data has different format:

Type 4 is usually used to send text data, which is probably the reason of the resource size being increased by one (for null terminator). Client sends a list of such resources to the C2. We were able to identify the meaning of some of them:

- DGA seed

- number of seconds since malware start

- Unix timestamp of malware start

- OS version and its default language

- computer’s IP (local if behind NAT)

- UDP port used to listen for P2P connections

- custom hash of current peer list

The server response uses a very similar format. The payload also depends on request type – if it was 1 (download file request), server responds with that file’s contents (usually compressed, depending on flags). For command request, the server response is the list of resources in the same format as above. Some of these resources can be interpreted as commands to be executed, for example “sleep N milliseconds” or “log off the user” (although I did not see the latter used in the wild).

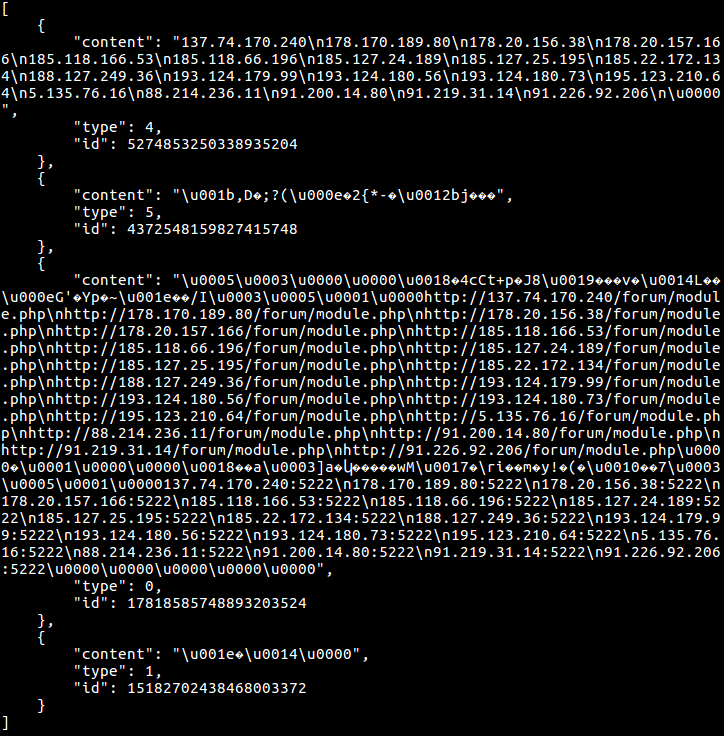

Sample (parsed) resource list received from C2:

Out of a large number of possible resources, the most important are the new peer list (only if its hash differs from current), or announcement of a new DLL being available to download. The latter resource has its own structure for communication purposes (a real matrioshka!), also made of a list of concatenated sub-resources of the following form:

The command can be interpreted as a request for running DLL identified by its SHA-1 with command line parameters stated in cmdline field – in practice, the argument is a newline-separated list of C2 addresses (with HTTP path) to be connected to.

Spam C2 communication

The last protocol I will describe in this post, is the communication of the downloaded DLL module, whose responsibility is to send spam emails. The information is wrapped in the following structure (sent as POST data over HTTP):

The encryption algorithm:

After decryption, there are no more steps – we receive raw data as a JSON string (unless the compression flag was set, in which case the data needs to be unpacked – as we found out, a QuickLZ library was used in the malware for this purpose). Unfortunately, keys are obfuscated, so we had to guess their meaning. Sample JSON (pretty-printed and edited to fit on screen):

Finally, one of the fields in the received dictionary contains a script used to generate randomized emails (like on the top of the post), and as another field – list of parameters passed to this script (e.g. eng_Names). We can make a separate request to download value of these arguments – as a response, we will receive, for example, list of English names to be substituted, or a few base64-encoded files to be used as an attachment.

Example communication

I’m aware understanding all those structures and ways they are used is quite hard, so I have created a simplified graph showing the data flow. Example communication could look like this:

fe929245ee022e3410b22456be10c4f1 - original file (packed)

35be639c5618272f70a0bbfbc25d4465 - dropped DLL module

YARA rules: