Intro

Dridex mostly comes to us as spam which contains a .doc with some macros, responsible for downloading a dropper. One can quickly analyze it using oledump.py and looking through vbscript, or naturally, just try to run it in a sandbox and obtain the dropped files.

CFG extraction

After unpacking the rather mundane packer, lets get into the juicy parts. We are presented with a small stage1 dropper, which looks rather basic.

The purpose of the dropper is to download the main binary from C&C and inject it to explorer, plus some generic initialization stuff.

First lets take a look how to find C&C addresses. In older samples there was a PE section called .sdata and it contained xored xml-document with all of the interesting data,

<server_list>

85.25.238.9:8843

91.142.221.195:5445

46.37.1.88:473

</server_list>

</config>

About a week ago that changed. There is no more .sdata – data sits in plain sight somewhere in memory, structured as follows:

| struct cfg_t { |

| int field_0; |

| unsigned __int16 botnet; |

| unsigned __int8 count; |

| char unknown; |

| ip_addr cnc[count]; |

| }; |

| struct ip_addr { |

| char ipaddr[4]; |

| __int16 port; |

| }; |

Using a yara signature like this:

$new_get_cnc = { E8 [4] BE [4] 8D ?? 5B 83 C4 1C 0F [3] 08 0F [3] 09 0F [3] 0A 0F [3] 0B 0F [3] 0C }

we can easily locate address where it is used and pull out that data.

First encounter with C&C

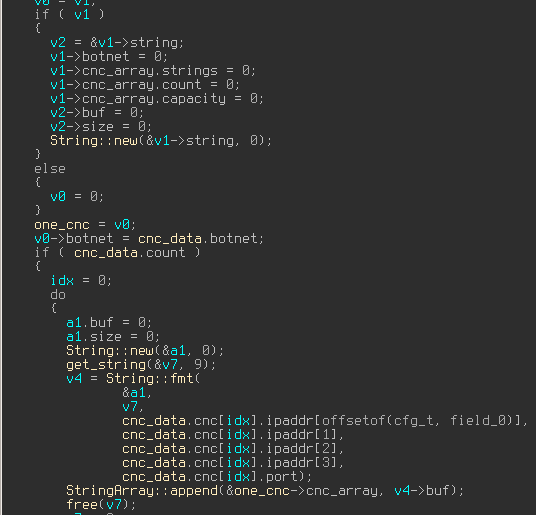

Ok, now we have to find code that calls those addresses. After going back-and-forth between references we stumble across this function:

Here is a little digression, if you don’t know this already: Dridex uses encoded strings and a run-time api resolving to make our life harder. Fortunately nothing fancy, a simple xor:

| def dridex_decode_name(addr,idx,delm=“\x00“): |

| addr += 8; tmp = ‘‘; j = 0 |

| xkey = GetManyBytes(addr,8) |

| for i in range(idx+1): |

| tmp = ‘‘ |

| while not tmp.endswith(delm): |

| tmp += chr(ord(xkey[j%8]) ^ Byte(addr+8+j)) |

| j+=1 |

| return tmp.strip(delm) |

Back to business. Despite what’s often reported, the first communication is not encrypted with xor as described in other articles, but with RC4. Keys are stored somewhere in binary encoded as any other string. They are different per botnet but otherwise don’t seem to change that often. For botnet 220 the key is:

ub9sKhcvsePZXuFC4HRw8KjFSIVUxsdAJXFyVP3Acl7HYL9KQBzETBzFvk2FlxeHZFBljIPps21W

Armed with C&C addresses and key, we can create a message. Fortunately, the Dridex authors were kind enough not to use any fancy binary format, just plain xml (sometimes gziped but we got to that part later…) and the message looks something like this:

<get_module unique=”%s” botnet=”%d” system=”23128″ name=”%s” bit=”32″/>

<soft><![CDATA[]]></soft>

</loader>

where “unique” is a bot name, created as follows:

“botnet” is a 2 bytes value hidden in config, and the name corresponds to a request we’d like to do.

The most basic request is `list` which obtains a list of nodes.

After decrypting the response, using RC4 with the same key, we got something like this, base64-encoded string is copied without decoding and dealt with in the next stage.

<module name=”list”>

Apts4+yozUR8Nbcan9dOya6yFIq6mxfdnJjlydF+uAELwWrIEIcvQIkk1mPURXr25/IwtnDW9l4s36C1

0iL0O6H3sJ1xhnUvcLN7ccjZU+RNySaj6YYSALvTBcGfNreUusy1ESLHKscAq4LJqzNy3UoB6fHLyJkU

LKhVFpKnogyKQEt4lctDeIpAS3iKQwb3205JWYYEZMwTJQEzS9B29XQK6aa1VsPxFd31tsa7IPRFldSb

dDgUVQmVq35rDX5nJNAfOYttztqNC8etW0oDIxrkEzMJedOrGIIvAnMUtdjDeIouPdceNNhiLzkGY3q6

gQoV8pwkCQsSrwltmFOmbyW9l6Vx+XWBiD8wOROQS3iK

</module>

<root>

The next command is `bot` and is responsible for downloading main dll

|

1

|

<root><module name=”bot”>base64-string</module></root>

|

There is no rocket science here, base64-encoded string is being decoded and loaded into memory, what is interesting in this case is how it is done.

Loader

It is normal in the malware world to apply an extra layer of protection to files stored in the local system. For example Tinba additionally xors it’s configuration file with bot id. But a non-written rule of how most malware works, is that every code is passed through memory in clear text. As one can guess this not the case here.

Indeed, Dridex’es method of injecting into another process is quite nice. It consists of two stub loaders. The first is responsible of decoding real payload (again just xor), while the second is used as a simple pe-loader which makes it possible to run PE files without syscalls like LoadLibrary or CreateProcess.

This is clearly visible in any memory tracer,

…

[37ceca4ac82d0ade9bac811217590ecd.bin – 3980][3952]called[pre] NtWriteVirtualMemory(Explorer.EXE,1fe0000,459264) src: 932e90

…

[37ceca4ac82d0ade9bac811217590ecd.bin – 3980][3952]called[pre] NtWriteVirtualMemory(Explorer.EXE,b20000,2552) src: 12f348

…

[37ceca4ac82d0ade9bac811217590ecd.bin – 3980][3952]called[pre] NtWriteVirtualMemory(Explorer.EXE,b209f8,2460) sr c: 415020

…

[37ceca4ac82d0ade9bac811217590ecd.bin – 3980][3952]called[post] NtAllocateVirtualMemoryx(SELF,1900000,12288,MEM_COMMIT|MEM_RESERVE, RWX — )

[37ceca4ac82d0ade9bac811217590ecd.bin – 3980][3952]called[post] NtAllocateVirtualMemoryx(SELF,1910000,65536,MEM_COMMIT, RW- — )

What is important with further analysis is that it relays quite heavily on loader metadata, which is somehow modeled to resemble a legit PE – which obviously it is not, as it missed almost every PE characteristic besides the typical MZ-PE signature.

0000010: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 …………….

0000020: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 …………….

0000030: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 4000 0000 …………@…

0000040: 5045 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 PE…………..

0000050: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 …………….

0000060: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 …………….

0000070: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 …………….

0000080: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 …………….

0000090: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 …………….

00000a0: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 …………….

Main dll is obviously packed – however I leave that challenge to the reader as a homework, as this is the end of introduction. Cya in the next part!

mak

sample used,

|

1

|

37ceca4ac82d0ade9bac811217590ecd

|