Abstract: For the past two years we've been tinkering with a proof-of-concept decryptor for the Phobos family ransomware. It works, but is impractical to use for reasons we'll explain here. Consequently, we've been unable to use it to help a real-world victim so far. We've decided to publish our findings and tools, in hope that someone will find it useful, interesting or will continue our research. We will describe the vulnerability, and how we improved our decryptor computational complexity and performance to reach an almost practical implementation. The resulting proof of concept is available at CERT-Polska/phobos-cuda-decryptor-poc.

When, what and why

Phobos is the innermost and larger of the two natural satellites of Mars, with the other being Deimos. However, it's also a widespread ransomware family that was first observed in the early 2019. Not a very interesting one – it shares many similarities with Dharma and was probably written by the same authors. There is nothing obviously interesting about Phobos (the ransomware) – no significant innovations or interesting features.

We've started our research after a few significant Polish organizations were encrypted by Phobos in a short period of time. After that it has become clear, that the Phobos' key schedule function is unusual, and one could even say – broken. This prompted us to do further research, in hope of creating a decryptor. But let's not get ahead of ourselves.

Reverse Engineering

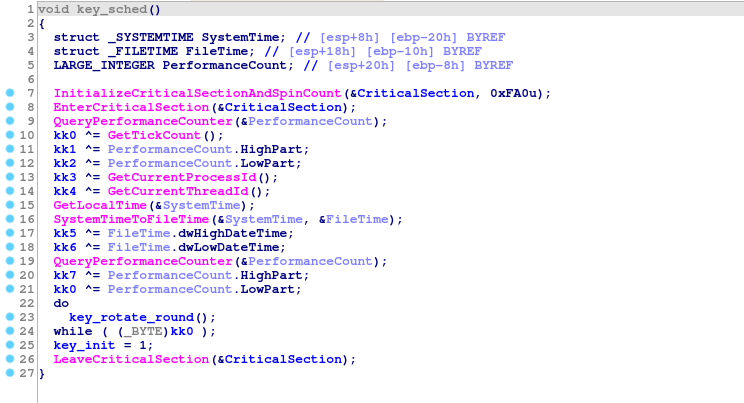

Let's skip the boring details that are the same for every ransomware (anti-debug features, deletion of shadow copies, main disk traversal function, etc). The most interesting function for us right now is the key schedule:

The curious part is that, instead of using one good entropy source, malware author decided to use multiple bad ones. They include:

- Two calls to QueryPerformanceCounter()

- GetLocalTime() + SystemTimeToFileTime()

- GetTickCount()

- GetCurrentProcessId()

- GetCurrentThreadId()

Finally, a variable but deterministic number of SHA-256 rounds is applied.

On average, to check a key we need 256 SHA-256 executions and a single AES decryption.

This immediately sounded multiple alarms in our heads. Assuming we know the time of the infection with 1 second precision (for example, using file timestamps, or logs), the number of operations needed to brute-force each component is:

| Operation | No. operations |

|---|---|

| QueryPerformanceCounter 1 | 10**7 |

| QueryPerformanceCounter 2 | 10**7 |

| GetTickCount | 10**3 |

| SystemTimeToFileTime | 10**5 |

| GetCurrentProcessId | 2**30 |

| GetCurrentThreadId | 2**30 |

It's obvious, that every component can be brute-forced independently (10**7 is not that much for modern computers). But can we recover the whole key?

Assumptions, assumptions (how many keys do we actually need to check?)

Initial status (141 bits of entropy)

But by a simple multiplication, number of keys for a naïve brute-force attack is:

>>> 10**7 * 10**7 * 10**3 * 10**5 * 2**30 * 2**30 * 256

2951479051793528258560000000000000000000000

>>> log(10**7 * 10**7 * 10**3 * 10**5 * 2**30 * 2**30 * 256, 2)

141.08241808752197 # that's a 141-bit number

This is... obviously a huge, incomprehensibly large number. No slightest chance to brute-force that.

But we're not ones to give up easily. Let's keep thinking about that.

May I have your PID, please? (81 bits of entropy)

Let's start with some assumptions.

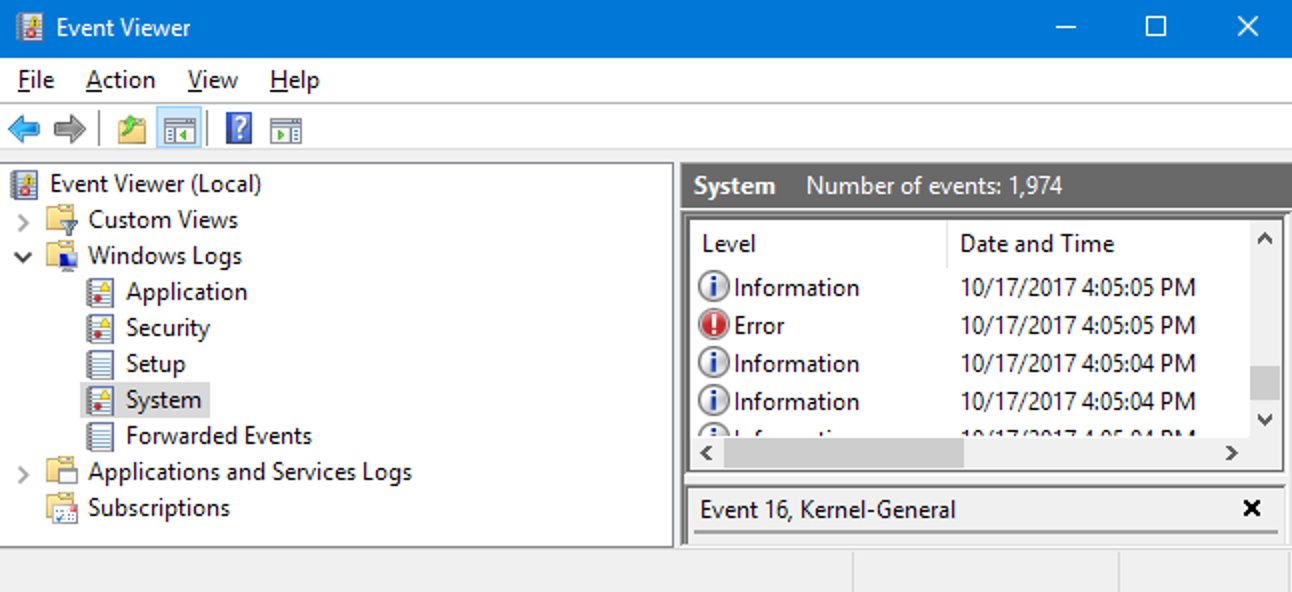

We already made one: thanks to system/file logs we know the time with 1 second precision. One such source can be the Windows event logs:

By default there is no event that triggers for every new process, but with enough forensics analysis it's often possible to recover PID and TID of the ransomware process.

Even if it's not possible, it's almost always possible to restrict

them by a significant amount, because Windows PIDs are sequential. So we won't usually have

to brute-force full 2**30 key space.

For the sake of this blog post, let's assume that we already know PID and TID (of main thread) of the ransomware process. Don't worry, this is the biggest hand-wave in this whole article. Does it make our situation better at least?

>>> log(10**7 * 10**7 * 10**3 * 10**5 * 256, 2)

81.08241808752197

81 bits of entropy is still way too much to think about brute-forcing, but we're getting somewhere.

Δt = t1 - t0 (67 bits of entropy)

Another assumption that we can reasonably make, is that two sequential

QueryPerformanceCounter calls will return similar results. Specifically,

second QueryPerformanceCounter will always be a bit larger than the

first one. There's no need to

do a complete brute-force of both counters – we can brute-force the first

one, and then guess the time that passed between the executions.

Using code as an example, instead of:

for qpc1 in range(10**7):

for qpc2 in range(10**7):

check(qpc1, qpc2)

We can do:

for qpc1 in range(10**7):

for qpc_delta in range(10**3):

check(qpc1, qpc1 + qpc_delta)

10**3 was determined to be enough empirically. It should be enough in most

cases, though it's just 1ms, and so it will fail in an event of a very unlucky context

switch. Let's try though:

>>> log(10**7 * 10**3 * 10**3 * 10**5 * 256, 2)

67.79470570797253

Who needs precise time, anyway? (61 bits of entropy)

2**67 sha256 invocations is still a lot, but it's getting manageable.

For example, this is coincidentally almost exactly the current BTC hash rate.

This means, if the whole BTC network was repurposed to decrypting Phobos victims instead of pointlessly burning electricity, it would decrypt one victim per second1.

Time for a final observation: SystemTimeToFileTime may have a precision

equal to 10 microseconds. But GetLocalTime does not:

This means that we only need to brute-force 10**3 options, instead

of 10**5:

>>> log(10**7 * 10**3 * 10**3 * 10**3 * 256, 2)

61.150849518197795

Math time (51 bits of entropy)

There are no more obvious things to optimize. Maybe we can find a better algorithm somewhere?

Observe that key[0] is equal to GetTickCount() ^ QueryPerformanceCounter().Low.

Naive brute-force algorithm will check all possible values for both components,

but in most situations we can do much better. For example, 4 ^ 0 == 5 ^ 1 == 6 ^ 2 = ... == 4.

We only care about the final result, so we can ignore timer values that end up as the same key.

Simple way to do this looks like this:

def ranges(fst, snd):

s0, s1 = fst

e0, e1 = snd

out = set()

for i in range(s0, s1 + 1):

for j in range(e0, e1 + 1):

out.add(i ^ j)

return out

Unfortunately, this was quite CPU intensive (remember, we want to squeeze as much performance as possible). It turns out that there is a better recursive algorithm, that avoids spending time on duplicates. Downside is, it's quite subtle and not very elegant:

uint64_t fillr(uint64_t x) {

uint64_t r = x;

while (x) {

r = x - 1;

x &= r;

}

return r;

}

uint64_t sigma(uint64_t a, uint64_t b) {

return a | b | fillr(a & b);

}

void merge_xors(

uint64_t s0, uint64_t e0, uint64_t s1, uint64_t e1,

int64_t bit, uint64_t prefix, std::vector<uint32_t> *out

) {

if (bit < 0) {

out->push_back(prefix);

return;

}

uint64_t mask = 1ULL << bit;

uint64_t o = mask - 1ULL;

bool t0 = (s0 & mask) != (e0 & mask);

bool t1 = (s1 & mask) != (e1 & mask);

bool b0 = (s0 & mask) ? 1 : 0;

bool b1 = (s1 & mask) ? 1 : 0;

s0 &= o;

e0 &= o;

s1 &= o;

e1 &= o;

if (t0) {

if (t1) {

uint64_t mx_ac = sigma(s0 ^ o, s1 ^ o);

uint64_t mx_bd = sigma(e0, e1);

uint64_t mx_da = sigma(e1, s0 ^ o);

uint64_t mx_bc = sigma(e0, s1 ^ o);

for (uint64_t i = 0; i < std::max(mx_ac, mx_bd) + 1; i++) {

out->push_back((prefix << (bit+1)) + i);

}

for (uint64_t i = (1UL << bit) + std::min(mx_da^o, mx_bc^o); i < (2UL << bit); i++) {

out->push_back((prefix << (bit+1)) + i);

}

} else {

merge_xors(s0, mask - 1, s1, e1, bit-1, (prefix << 1) ^ b1, out);

merge_xors(0, e0, s1, e1, bit-1, (prefix << 1) ^ b1 ^ 1, out);

}

} else {

if (t1) {

merge_xors(s0, e0, s1, mask - 1, bit-1, (prefix << 1) ^ b0, out);

merge_xors(s0, e0, 0, e1, bit-1, (prefix << 1) ^ b0 ^ 1, out);

} else {

merge_xors(s0, e0, s1, e1, bit-1, (prefix << 1) ^ b0 ^ b1, out);

}

}

}

It's possible that there exists a simpler or faster algorithm for this problem, but authors were not aware of it when working on the decryptor. Entropy after that change:

>>> log(10**7 * 10**3 * 10**3 * 256, 2)

51.18506523353571

This was our final complexity improvement. What's missing is a good implementation

Gotta go fast (how fast can we go?)

Naïve implementation in Python (500 keys/second)

Our initial PoC written in Python tested 500 keys per second. Quick calculation shows that this brute-forcing 100000000000 keys will take 2314 CPU-days. Far from practical. But Python is basically the slowest kid in on block as far as high performance computing goes. We can do much better.

Usually in situations like this we would implement a native decryptor (in C++ or Rust). But in this case, even that would not be enough. We had to go faster.

Time works WONDERS

We've decided to go for maximal performance and implement our solver in CUDA.

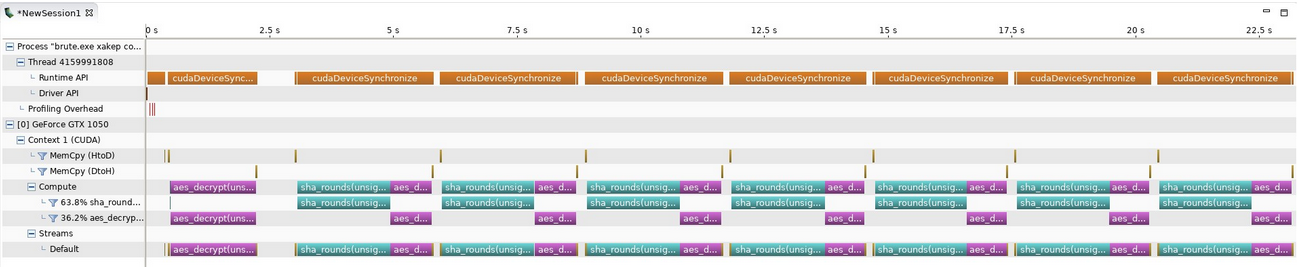

CUDA first steps (19166 keys/minute)

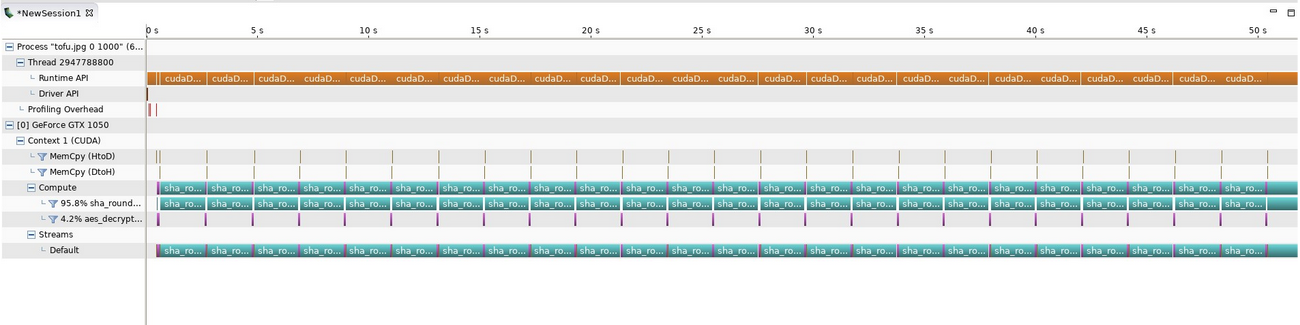

Our first naive version was able to crack 19166 keys/minute. We had no experience with CUDA at the time, and made many mistakes. Our GPU utilization stats looked like this:

Improving sha256 (50000 keys/minute)

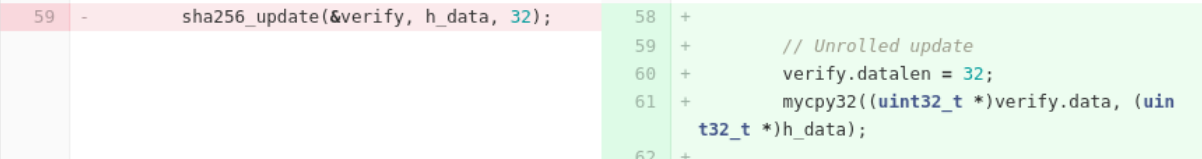

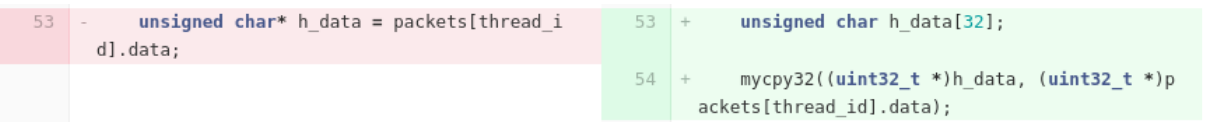

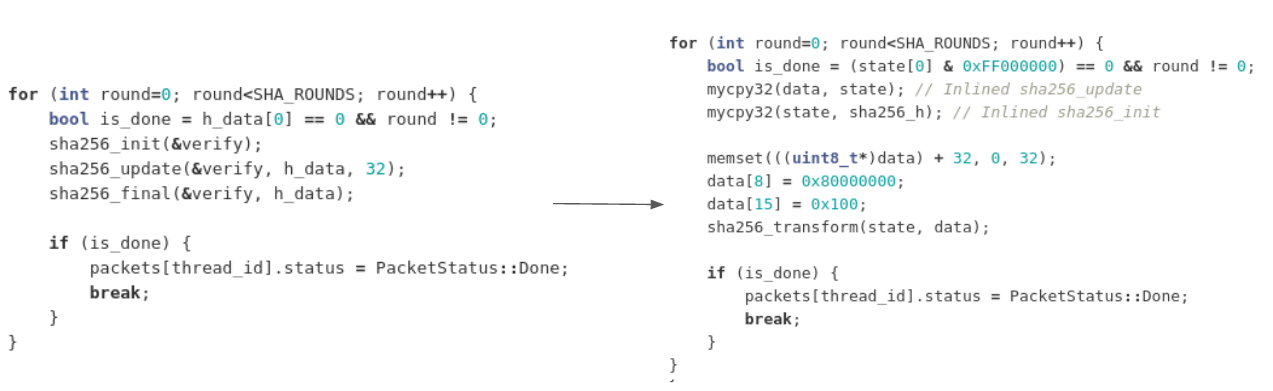

Clearly sha256 was a huge bottleneck here (not surprisingly – there are 256 times more sha256 calls than AES calls). Most of our work here focused on simplifying the code, and adapting it to the task at hand. For example, we inlined sha256_update:

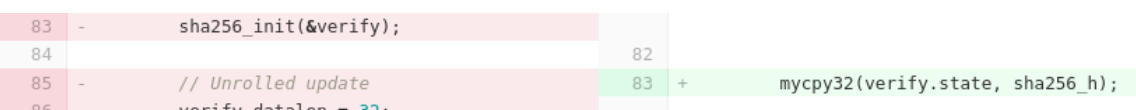

We inlined sha256_init:

We replaced global arrays with local variables:

We hardcoded data size to 32 bytes:

And made a few operations more GPU-friendly, for example used __byte_perm for bswap.

In the end, our main loop changed like this:

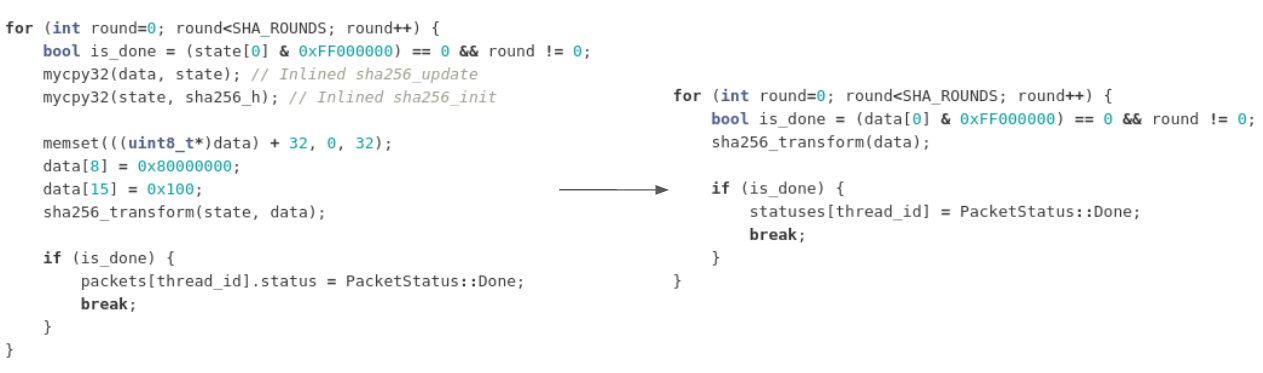

But that's not the end - after this optimization we realized that the code is now making a lot of unnecessary copies and data transfers. There are no more copies needed at this point:

Combining all this improvements let us improve the performance 2.5 times, to 50k keys/minute.

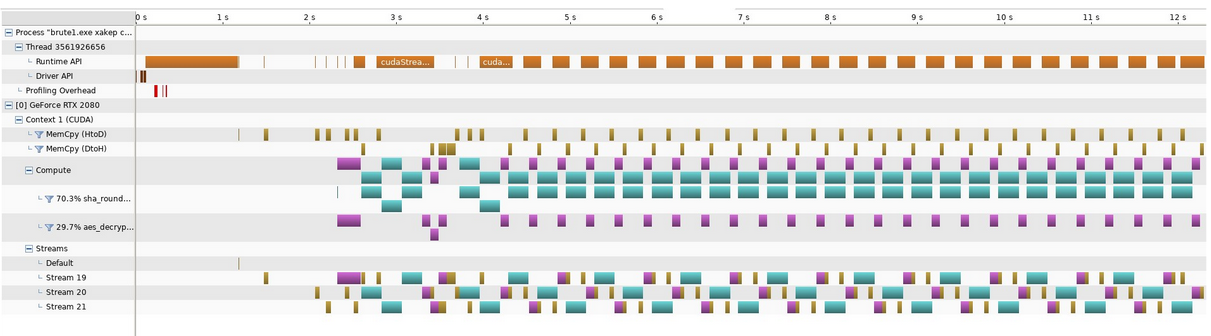

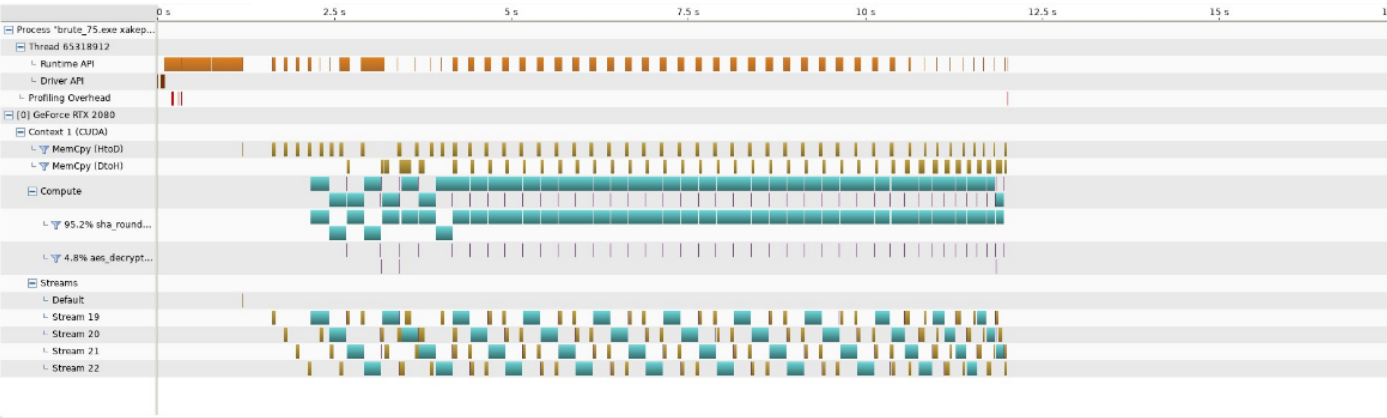

Now make it parallel (105000 keys/minute)

It turns out graphic cards are highly parallel. Work is divided into streams, and streams are doing the logical operations. Especially memcopy to and from graphic card can execute at the same time as our code with no loss of performance.

Just by changing our code to use streams more effectively, we were able to double our performance to 105k keys/minute:

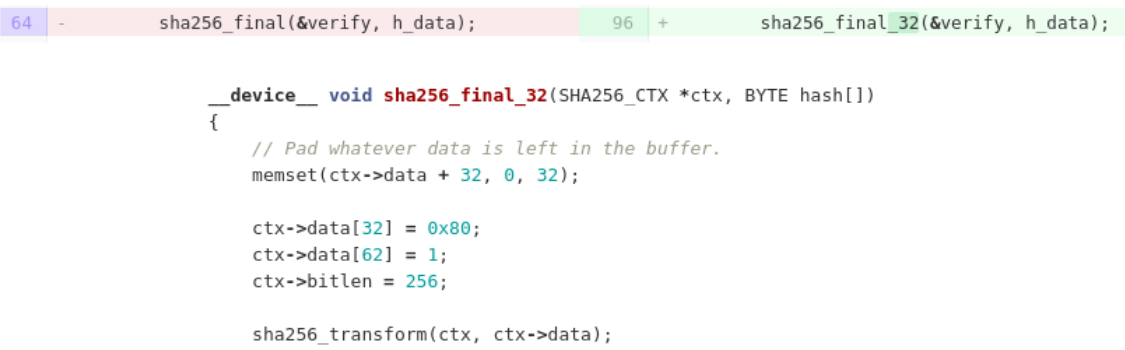

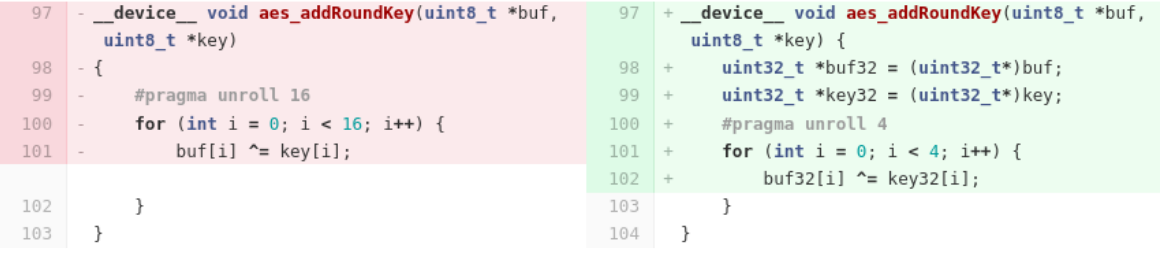

And finally, AES (818000 keys/minute)

With all these changes, we still didn't even try optimizing the AES. After all the lessons learned previously, it was actually quite simple. We just looked for patterns that didn't work well on GPU, and improved them. For example:

We changed a naive for loop to manually unrolled version that worked on

32bit integers.

It may seem insignificant, but it actually dramatically increased our throughput:

...and now do it in parallel (10MM keys/minute)

At this point we were not able to make any significant performance improvements anymore. But we had one last trick in our sleeve - we can run the same code on more than one GPU! Conveniently, we have a small GPU cluster at CERT.PL. We've dedicated two machines with a total of 12 Nvidia GPUs to the task. By a simple multiplication, this immediately increased our throughput to almost 10 million keys per minute.

So brute-forcing 100000000000 keys will take just 10187 seconds (2.82 hours) on the cluster. Sounds great, right?

Where Did It All Go Wrong?

Unfortunately, as we've mentioned at the beginning, there are a lot of practical problems that we skimmed over in this blog post, but that made publishing the decryptor tricky:

- Knowledge of TID and PID is required. This makes the decryptor hard to automate.

- We assume a very precise time measurements. Unfortunately, clock drift and intentional noise introduced to performance counters by Windows makes this tricky.

- Not every Phobos version is vulnerable. Before deploying a costly decryptor one needs a reverse engineer to confirm the family.

- Even after all the improvements, the code is still too slow to run on a consumer-grade machine.

- Victims don't want to wait for researchers without a guarantee of success.

This is why we decided to publish this article and source code of the (almost working) decryptor. We hope that it will provide some malware researches a new look on the subject and maybe even allow them to decrypt ransomware victims.

We've published the CUDA source code in a GitHub repository: https://github.com/CERT-Polska/phobos-cuda-decryptor-poc. It includes a short instruction, a sample config and a data set to verify the program.

Let us know if you have any questions or if you were able to use the script in any way to help a ransomware victim. You can contact us at [email protected].

Ransomware sample analyzed: 2704e269fb5cf9a02070a0ea07d82dc9d87f2cb95e60cb71d6c6d38b01869f66 | MWDB | VT

-

Assuming, of course, that we know PID and TID, and ignoring the cost of AES decryption to verify key candidates. Just a thought experiment anyway. ↩